This is the first in a series of four blog posts to introduce the underpinning concepts related to variation in systems. In this post we discuss common cause and special cause variation.

These concepts provide a foundation for understanding and responding to variation in systems. In particular these concepts are fundamental to understanding the notions of stability, capability and avoiding tampering; each of which will be discussed in subsequent posts.

We also discuss simple tools that allow us to ‘see the variation’ in systems and processes. Understanding and applying these concepts and tools helps us to respond appropriately to data to continually improve, rather than risk making things worse!

Variation is everywhere

Variation is evident in all systems. No two real things are identical.

Consider, for example, the standard AA size battery. AA size batteries are 50 mm long and 14 mm in diameter, as defined by international standards. They all look the same and are perfectly interchangeable. Yet each individual battery cannot be exactly 50 mm long and exactly 14 mm in diameter. Most people don’t care that one battery is 50.013 mm long and another is 49.957 mm long; both will fit perfectly well in their flashlight or remote control. To detect these differences – the variation – precise measuring equipment is required.

A factory will produce batteries with a length that has a calculable mean, an observable spread, and a clustering of lengths around the mean. All determined by the manufacturing process.

While two observed things are never identical, we can think of them as being identical when our measurement system is unable to detect difference, or when any differences are of no practical significance.

Sometimes variation is more evident. The average height of an Australian 13-year-old boy is approximately 156 cm. Very few 13-year old boys are precisely 156 cm tall, but nearly all will be within about three cm of this average height. This phenomenon is known as the natural limits of variation. In this case; a typical 13 year old boy’s height falls naturally within a range of heights centered at 156 cm and varying up to about three cm above and below this value.

All processes and systems exhibit natural variation. In both these examples, a battery’s dimensions and the height of a 13-year-old boy, the characteristic being measured is different from observation to observation. Yet, as a set of observations they conform to a defined distribution, in this case the normal distribution.

The factors that cause this variation, from observation to observation, come from the system. In the case of AA batteries, it is the system of manufacturing; variation in the height of 13-year-old boys comes from genetic, societal and environmental factors. In both cases, it is the system that produces natural variation.

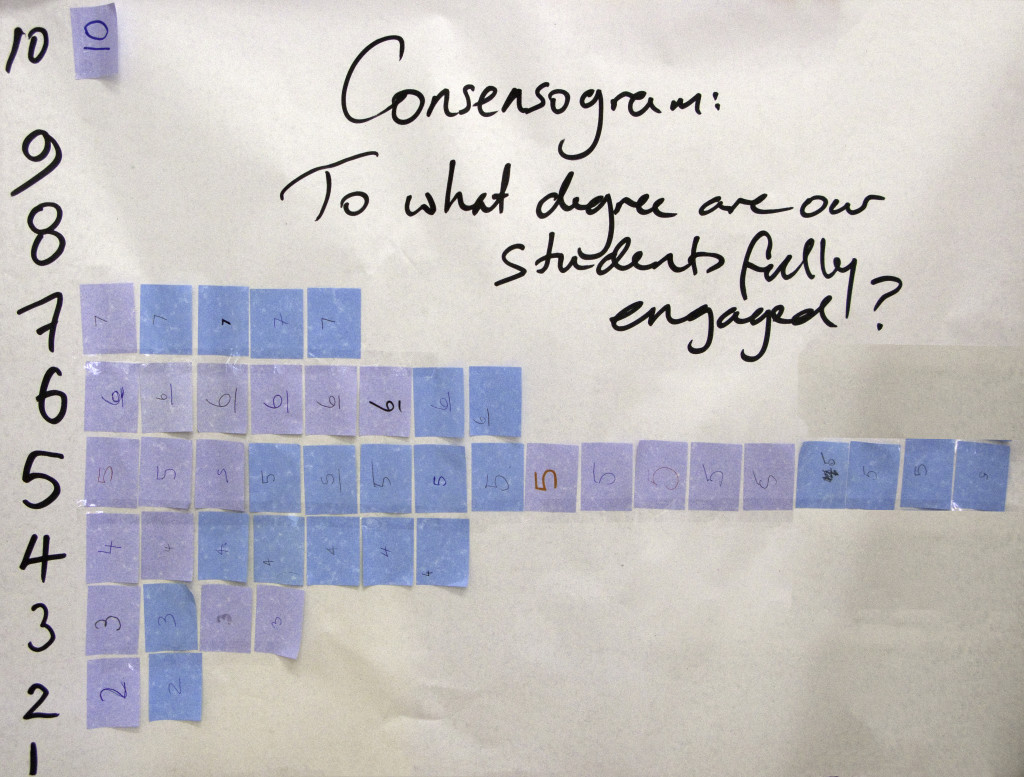

In a similar manner, systems produce variation in perceptions and performance. Figure 1 shows the perceptions of teachers in a school regarding the degree of engagement of their students. The variation in perceptions is evident.

It is the system that produces natural variation. To understand this variation, it is necessary to understand the system. No examination of individual examples can explain the system.

Common cause variation

Variation observed in any system comes from diverse and multitudinous possible causes.

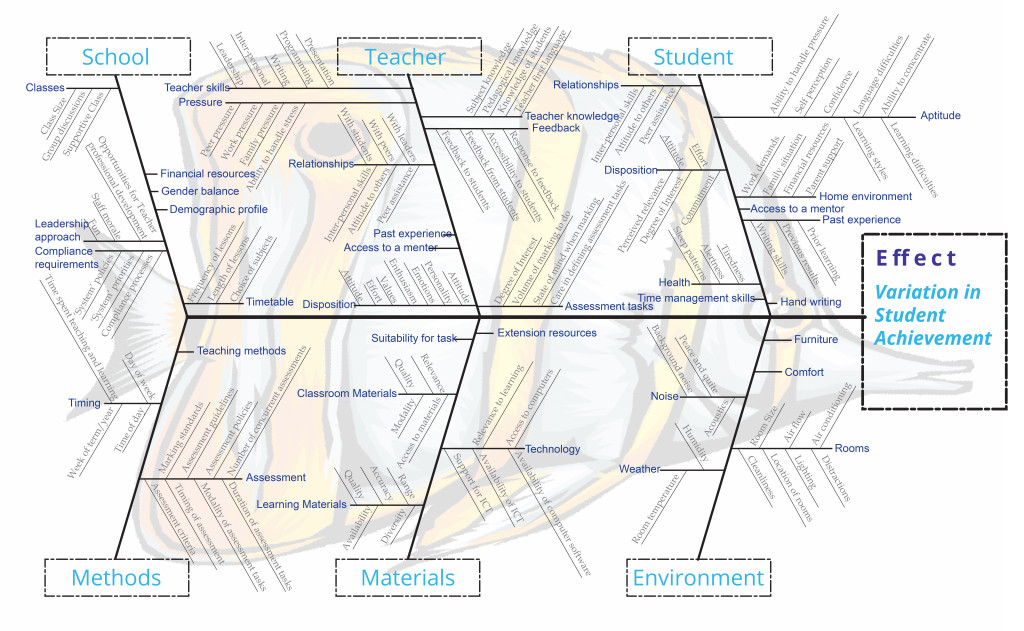

The fishbone diagram can be used to document the many possible causes of variation. The fishbone diagram in Figure 2, for example, lists possible causes of variation in student achievement.

Each of the causes affects every student to a greater or lesser degree. Students respond to each cause in different ways, so the impact is different for each student. For example, some students may be sensitive to background noise while others are not. Some students may struggle to balance family responsibilities, work and school, while for others this not an issue. All students will be affected to some degree by their prior learning and their attitude towards the subject matter. The key point, however, is that every student may be affected to some degree by every cause. It is how all of the causes come together for each individual student that results in the variation in student achievement observed across the class. Causes that affect every observation, to greater or lesser degrees, are called common causes.

Common cause variation is the variation inherent in a system. It is always present. It is the net result of many influences, most of which are unknown.

In general, it is the combination of the common causes of variation coming together uniquely for each observation that results in the distribution in the set of data points. That is, the set of observations conform to a defined distribution. Not surprisingly, this distribution is frequently a normal distribution.

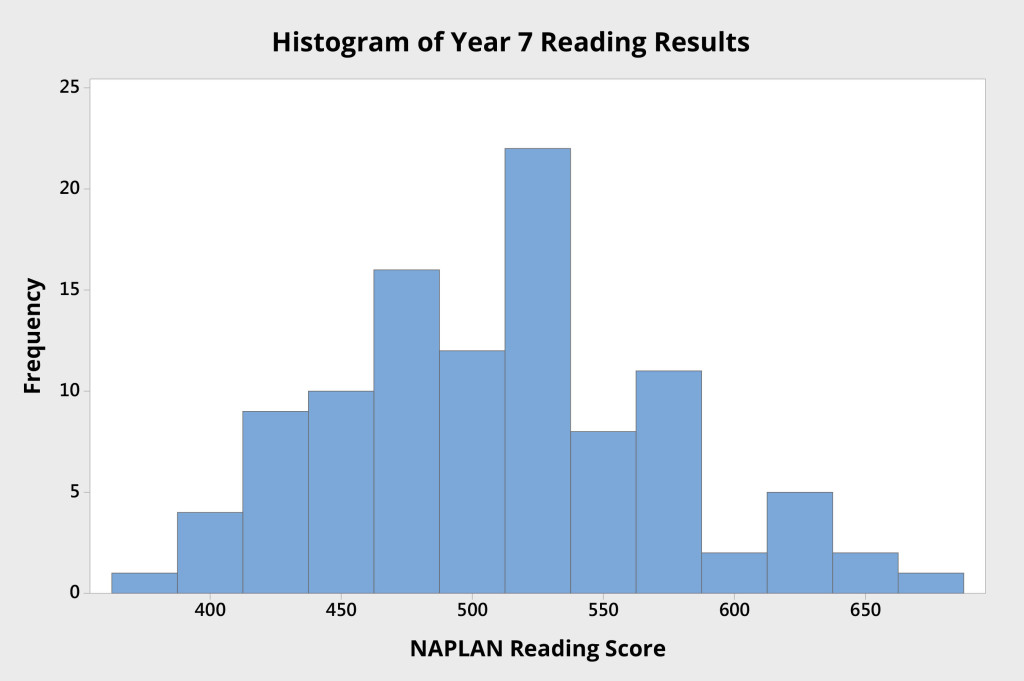

Figure 3 shows a histogram or frequency chart of the variation in year 7 students’ reading test scores from an Australian school, as measured by a national standard test. You can see the natural spread of variation in this measure of the students’ reading performance.

For any single data point — for example, a single student’s test result — it is not possible to identify any specific cause that led to the result achieved. Importantly, it is not worth trying to identify any such single cause.

The system of common causes determines the behaviour and performance of the system. These causes include the actions and interactions among the elements of the system, as well as features of the structure of the system and those of the containing systems.

Special cause variation

The other type of variation is special cause variation.

When a cause can be identified as having an outstanding and isolated effect — such as a student being late to school on the morning of an assessment — this is called special cause variation or assignable cause variation. A specific reason can be assigned to the observed variation.

Special cause variation is variation that is unusual and unpredictable. It can be the result of a unique event or circumstance, which can be attributed to some knowable influence. It is also known as assignable cause variation.

Special causes of variation are identifiable events or situations that produce specific results that are out of the ordinary. These out of the ordinary results may be single points of data beyond the natural limits of variation of the system, or they may be observable patterns or trends in the data.

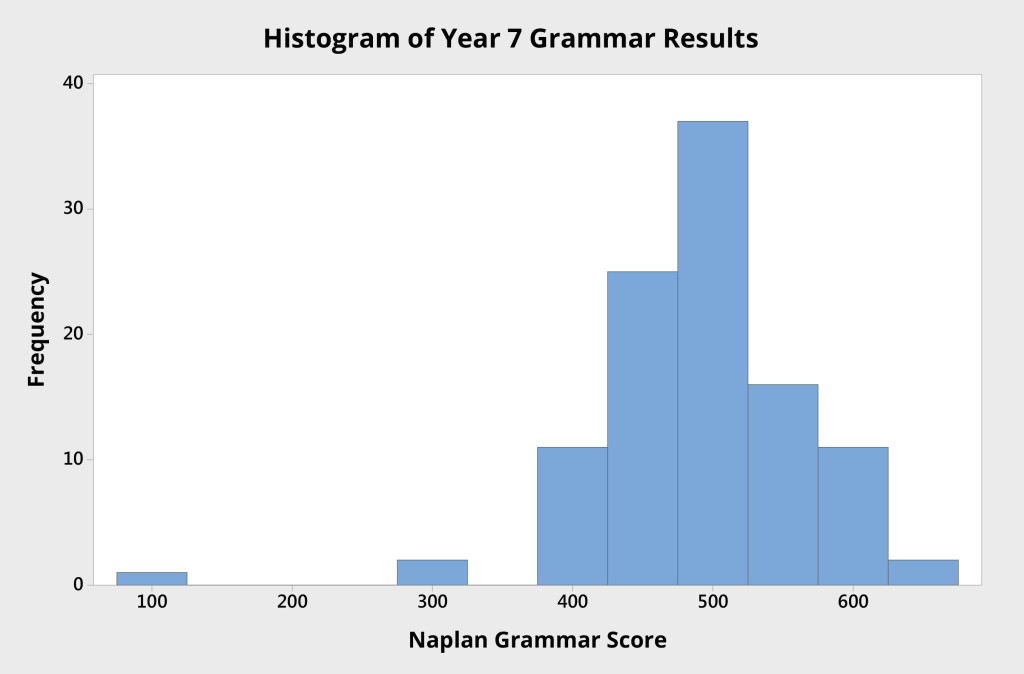

Figure 4 hows a histogram or frequency chart of the variation in year 7 students’ grammar test scores from the same Australian school, as measured by a national standard test. You can see the natural spread of variation in this measure of the students’ grammar achievement. You can also see one student’s results significantly below the vast majority of scores. That single observation suggests a special cause of variation and is worthy of investigation.

Where there is evidence of special cause variation in a set of data, it is always worth investigating. The impact of a special cause may be detrimental, in which case it may be appropriate to seek to prevent occurrence of this cause within the system. The impact of a special cause may also be beneficial, in which case it may be worth pursuing how this cause can be harnessed to improve system performance.

Special causes provide opportunities to learn. The lesson might be as mundane as “that batch of electrolyte was contaminated”, or it might be as exciting as the discovery of penicillin, or a new strategy for learning.

In summary:

Variation is evident in all observations – from physical dimensions to student behaviour and academic achievement. Most observed variation is due to common causes – those causes that affect every observation, to differing degrees. Sometime, there are specific and identifiable causes of variation – these are known as special causes.

These two key concepts – common and special cause variation – are fundamental to responding to system variation appropriately. An understanding of these concepts is critical to affecting demonstrable and sustainable improvement. They underpin an understanding of system stability, capability and tampering, which will each be discussed in future blog posts. Where these concepts are not understood, attempts to improve performance frequently make things worse.

Download a Fishbone Diagram template.

Read about Four types of measures, and why you need them.

Read more in our comprehensive resource, IMPROVING LEARNING: A how-to guide for school improvement.

Purchase our learning and improvement guide: Using data to improve.

2 thoughts on “Understanding Variation 1 – common and special cause variation”