This is the final of a series of four posts to explore human motivation, and how we can encourage learners’ intrinsic motivation and engagement. These posts are edited extracts from our forthcoming book: Improving Learning: A how-to guide for school improvement.

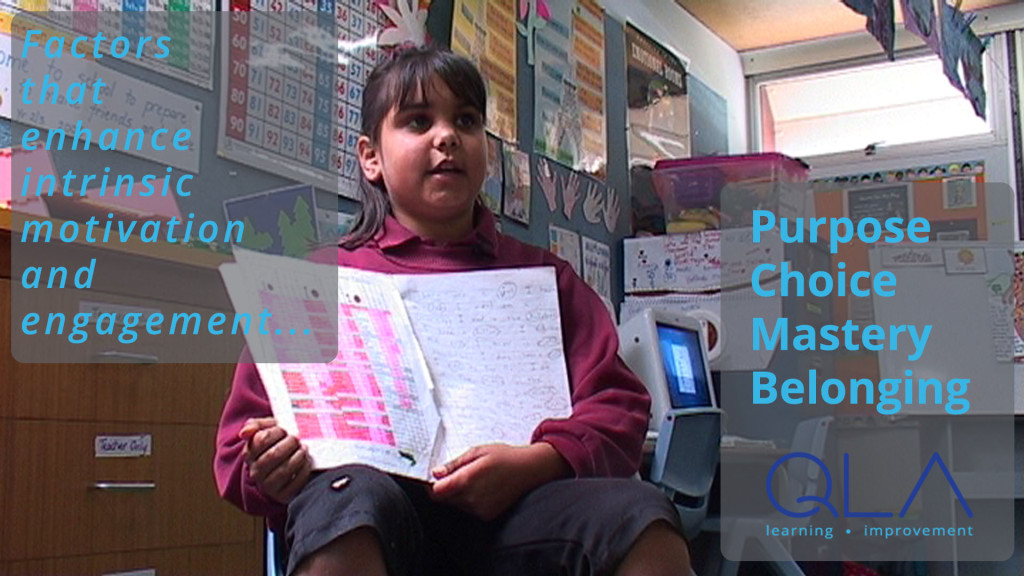

In the previous posts we introduced the concepts of motivation, rewards, punishment, compliance and engagement. We explored a framework of factors to enhance intrinsic motivation and engagement, namely: Purpose, Choice, Mastery and Belonging.

In this post we conclude with an examination of the use of rewards in classrooms and how these can be substituted for working with students to identify and remove barriers to motivation and engagement.

Rewards in schools

The use of extrinsic rewards in schools and school systems is very deeply ingrained.

Many classroom teachers offer extrinsic rewards regularly as part of their behaviour management approach. From a very early age, students learn to please the teacher in order to be rewarded. Gold stars, lolly jars, student of the week, bonus points and free choice activities are offered as incentives. Teachers have been taught to do this; rewards are common practice. This diminishes the important intrinsic reward that comes from learning. Learning soon becomes more about work to please the teacher than personal growth and achievement.

When teachers are asked why they use extrinsic rewards, such as stickers, lollies, bonus points, or classroom parties, the answer is always the same. ‘The kids like them and they work!’

Questionable assumptions

There are several assumptions that can be questioned here, assumptions about efficacy and motivation.

- ‘The kids like rewards!’ Just because someone likes something does not mean it is good for them, or that it helps them to learn. The more important question is whether rewards aid learning, and whether they offer a superior approach when compared to alternatives.

- Which kids like rewards? Obviously, the kids getting the rewards like it. There are very few people who don’t enjoy recognition, acknowledgement and being treated as a bit special. But what of those students who miss out? What of those students who are just as deserving but are not rewarded? How do they feel? Teachers are very busy watching the faces of the rewarded students and rarely notice the faces of the disappointed. Being disappointed repeatedly can be very demotivating.

- When teachers say the kids like rewards, one could ask ‘compared to what?’ Certainly, they could be expected to like getting rewards when compared to the option of not getting rewards. Who wouldn’t? But what about the option of getting rewards when compared to the option of discovering and experiencing the true joy of learning? Do the students have that reference point for comparison?

- What does it mean to say that the ‘rewards work’? Does this mean that student learning is enhanced by rewards? Or, does it mean that rewards encourage compliance? Most importantly, how do rewards improve learning compared to other approaches? As John Hattie is at pains to point out, nearly everything works in education; the real question is how well particular approaches enhance learning when compared to their alternatives.

- Rewards create energy for … more rewards. In an environment where rewards are common, so is the question ‘What do we get for doing this?’ In some cases, rewards can actually lower achievement, as students who are motivated by extrinsic rewards will do enough to get a reward, but no more, thereby artificially limiting their potential and motivation to achieve.

- Why are rewards necessary anyway? Do we really need to bribe people to do the right thing? Do people deliberately withhold best efforts and better methods waiting for the offer of a reward? Do students or teacher not try because they are hanging out for the reward to be offered? The answer to each of these questions is: ‘of course not!’

- An implicit assumption behind the offer of rewards is that people need rewards because they won’t do their best without them.

Myron Tribus makes explicit reference to the damage done by extrinsic motivators in his paper When Quality Goes to School.

Quality is what makes learning a pleasure and a joy.

You can increase some measures of performance by using strong external motivators, such as grades, prizes, threats and punishments, but the attachment to learning will be unhealthy.

It takes a joyful experience with learning to attach a student to education for life. Where there is joy in learning, the effort required does not seem like work.

Myron Tribus, When Quality Goes to School.

Intrinsic motivation in the classroom

Traditional didactic approaches to teaching do not promote intrinsic motivation. Some teachers churn through endless programs of plan-teach-assess in the hope that students will learn. If educators truly take to heart the need and moral obligation to unlock intrinsic motivation in learners, then a different approach is required. A more collaborative approach is needed.

Every learner is different, which adds enormously to both the joy and the complexity of teaching. The breadth and depth of prior knowledge varies, interests vary from student to student, as does the sense of belonging within a class or school. The home environment varies enormously too. Some families support and strongly encourage learning; others are less committed. How are teachers supposed to manage this variation? It can be extremely difficult to teach a class where the variation in knowledge and skills is measured in years of development.

The factors discussed in the previous two posts on motivation may be seen as requiring teachers to do even more than they do currently. How can teachers be expected to assess each factor on the model for each student for each learning activity and then respond to the findings? They cannot, it is too much to ask, even with small class sizes. This is not what we are advocating.

However, if teachers equip students to take responsibility for their learning and if teachers work with the students to adapt classroom processes, motivation and engagement can be continually improved.

Collaborating to remove barriers

Teachers and students can learn to work together in a more interdependent manner than the traditional student-teacher dependent relationship. This has been shown not to be additional work for teachers, just a different way of approaching their role. The key is to work with the students, which requires different relationships and the use of tools to support the collaboration.

As we pointed out in an earlier blog post, What the school improvement gurus are not yet talking about, students have an enormous contribution to make to school improvement.

This begins in the classroom, where students can work with the teacher to identify and remove barriers to motivation, engagement and learning. Students and teacher together explore the factors that enhance intrinsic motivation and engagement, and the degree to which they are evident in the school’s systems of learning. Together they develop and trial new tools and methods, make changes and observe the impact. In this way, they collaborate to study and improve the systems of learning that so profoundly affect them.

A Capacity Matrix is an example of a very useful tool. It helps learners understand what is to be learned and allows them to set goals and track progress.

Working with students to improve the system of learning opens new possibilities. Learning plans are routinely developed for students exhibiting special needs, but more recently there have been calls for all students to have individualised learning plans. Requiring teachers to develop the traditional individual learning plan for each of their students and then managing each plan is a practical impossibility. In the current system, teachers simply do not have the time to do this well for large numbers of students. But, there is nothing stopping students from learning how to develop and monitor their own individual learning plans.

Capacity Matrices can be used as the basis for individual learning plans for all students. Not only do the matrices make explicit what the students are expected to know, understand and be able to do, they significantly enhance intrinsic motivation. By design, their use is consistent with the factors that enhance intrinsic motivation and improvement. Capacity matrices make the aim or Purpose clear, students are given Choice in how they go about their learning, the matrices are explicitly designed to develop and demonstrate Mastery, and students’ sense of Belonging in enhanced through collaboration, feedback and support.

Our website includes several Capacity Matrix templates and many Capacity Matrix examples.